Blog

Svetislav Hodjera and the Yugoslav Popular Party – “borbašiˮ. The Forgotten “Apostles of a New Eraˮ

Rastko Lompar

Institute for Balkan Studies, SASA

Svetislav Hodjera and the Yugoslav Popular Party – “borbašiˮ. The Forgotten “Apostles of a New Eraˮ

In February 1975, as construction workers were digging through the cellar of a building that had just been torn down, they never suspected that they would come across a few thousand pages destined to save from oblivion a small yet belligerent political party that had championed integral Yugoslavism. A large-format tome luxuriously bound in leather covers embossed with the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia caught their eye. The volume contained minutes from the sessions of the Government of Petar Živković. How did it end up there, among those ruins? The papers scattered around it revealed the answer – these documents had belonged to Svetislav Hodjera, the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff. They are now kept in the Archive of Yugoslavia.

Svetislav Hodjera was born in Niš on November 12, 1888. Probably of non-Serbian extraction but a member of the Orthodox faith, he was educated in Niš, Belgrade and Paris. He studied law and, at the same time, worked as a bank clerk. The breakout of World War I in 1912 interrupted his education. As a student-sergeant in the cavalry regiment of the Timok Division, he fought in both Balkan wars, earning multiple medals.[1] He participated in the Serbian retreat across Albania and arrived at the Salonica (Macedonian) Front. He flew in a plane for the first time on the island of Corfu, later recalling: “It was then that I became an aviator and I knew I would fly. And that joy never left meˮ.[2] The Allied command decided that it was necessary to restore the Serbian fleet. Having completed his training, he became a member of the flight Ф.(3)98. On December 11, 1916, he was heavily wounded in an aerial battle with a German aircraft.[3] Svetislav Hodjera became the first Serbian serviceman wounded in air combat, a fact he would deftly use and frequently emphasize in his subsequent political career. His war efforts are on many levels important for understanding his political activities because the Great War left a deep mark on his personal development as the war in which he lost his “father, two brothers, and one brother-in-lawˮ, while another brother-in-law developed mental health problems at the Salonica Front.[4]

Once demobilized, he briefly renewed his diplomatic career and soon switched to practicing law. Besides working as a lawyer, he was involved in the organization and promotion of Yugoslav civil aviation. He co-founded the association “Naša Krilaˮ (Our Wings) and served as its deputy chairman for a long time; he was also the founder and one of the shareholders of the “Association for Air Travelˮ (1927).[5] In this association, later renamed “Aeroputˮ, he occupied various posts and long served as a member of its managing board.[6] He also worked to promote Yugoslav civil aviation, publishing articles on this subject in the papers Politika, Vreme, and Naša Krila.[7]

Svetislav Hodjera participated in the political life of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes as a member of the Local Committee of the People’s Radical Party (NRS) in Belgrade. His membership in a political party before the introduction of the king’s personal regime on January 6, 1929, could have hindered Hodjera’s political prospects after the restoration of parliamentarism in 1931 because he had mercilessly criticized “old men in politicsˮ and called on them to allow “new facesˮ to lead the country. Therefore, references to his membership in the People’s Radical Party, a potential burden in his political career, were cleverly avoided in his speeches and writings.[8] With the proclamation of the January Dictatorship, Svetislav Hodjera became the Chief of Staff under General Petar Živković, the chairman of the Council of Ministers. The available sources do not allow us to fully reconstruct what might have made him a suitable candidate for this position because the nature of his pre-1929 relationship with General Živković remains largely obscure. He served as the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff until the elections of 1931 when he ran for parliament as the deputy of the city of Peć. His election run was confirmed, and he defeated his only rival, Miloš Zonjić, by a landslide.[9]

After the elections, Svetislav Hodjera began to attract a group of younger deputies, MPs who were unhappy with the share of power they had in the government. They believed that the January manifest had placed them on the political stage and that they ought to be in charge of running the country instead of “old men in politicsˮ. Hodjera chaired the conferences that these disgruntled MPs held at Bristol Hotel in Belgrade, after which they came to be known as the “Bristoliansˮ and their group as the “Bristolian actionˮ. Since they controlled more than half of parliament seats (164), the government of Milan Srškić had no choice but to offer to negotiate in order to pacify them. The “Bristoliansˮ sent a seven-member delegation headed by Svetislav Hodjera. The talks lasted three days, and then six of the negotiators – all except Hodjera – accepted an agreement with the government; the deal was, according to Hodjera, “at odds with the given instructionsˮ. Once the talks ended, most “Bristoliansˮ went back to the government’s caucus, and Hodjera remained alone with nine of his closest associates. Hodjera later commented on the failure of the “Bristolian actionˮ: “when the fight between the old and the young broke out, and an open fight at that, the young gave in, surrendered and showed themselves incapable of fulfilling this great taskˮ.[10] With his supporters, gathered in the Yugoslav People’s Club, Hodjera continued his anti-government struggle in the parliament.

This small yet vocal group of MPs ultimately evolved into the Yugoslav Popular Party, which issued its first proclamation on June 3, 1933, launching its party organ Borba za slobodu, pravo i jednakost svih Jugoslovena (Struggle for the Freedom, Rights and Equality of all Yugoslavs).[11] The Ministry of the Interior approved the party in January 1934. Svetislav Hodjera became its president at the first congress (November 25, 1934). From the outset, the party faced accusations of being a “loyalˮ, “government-backedˮ or “falseˮ opposition, and the fact that it was headed by Petar Živković’s former Chief of Staff exacerbated these allegations. Despite harsh criticism, Svetislav Hodjera and his party comrades began to confront the MPs of the ruling Yugoslav Radical Peasants’ Democracy (later renamed the Yugoslav National Party –JNS). The first challenge was the imminent elections of 1935. The party launched an aggressive campaign in the field and, having collected a sufficient number of signatures, submitted its list of candidates, headed by Svetislav Hodjera, to the state organs for approval. At the elections of 1935, besides Bogoljub Jevtić’s ruling party, another participant was the previously extra-parliamentary opposition, having registered an electoral list headed by the Croatian leader Vladko Maček; Dimitrije Ljotić, Božidar Maksimović and Živko Topalović also submitted their own electoral lists. The Court of Cassation refused to confirm the lists of Živko Topalović and Svetislav Hodjera, citing technical flaws. Scholars have not reached a consensus about the reasons that led the court to discard the list of Hodjera and the Yugoslav Popular Party – borbaši (JNSb) and whether this was done with their consent.[12] I believe that the list was indeed refused partly due to technical flaws but also because the government had estimated that the majority of JNSb supporters would, in that case, vote for the government’s list. After having its complaint denied, the party issued a resolution calling on its supporters to vote for “the only opposition list left – Davidović-Mačekˮ.[13]

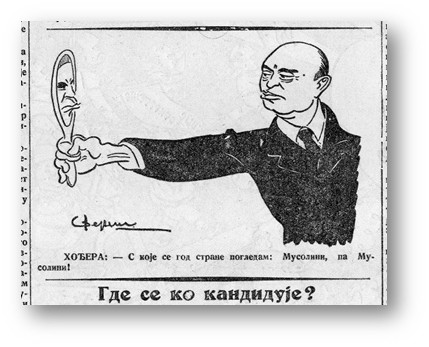

And so Hodjera and his associates remained on the electoral sidelines and with no seats in the parliament. They intensified their agitation among the people and began to launch attacks against the government while also having increasingly bitter confrontations with the United Opposition. These clashes were often fought in the streets, and the borbaši came to be known for their physical altercations with political opponents. Their use of violence and the blue shirts worn by the party’s supporters resulted in the branding of JNSb as a fascist party and Hodjera as “the only true Yugoslav fascistˮ.[14] The view that JNSb was indeed a fascist or Nazi group has become dominant in scholarship, although this has been contested at times.[15] The satirical monthly Ošišani jež (Bald Hedgehog) launched a particularly virulent campaign against Hodjera, portraying him as a fascist at whom the crowds throw eggs (Fig. 1; Fig. 2).

|

|

Fig. 1. Ošišani jež, April 20, 1935. |

Fig. 2. Ošišani jež, August 24, 1935 |

In the eyes of his supporters, Svetislav Hodjera was – at least nominally – a figure of utmost authority; they referred to him as “The Leaderˮ and often as “the protector of the poorˮ, “the new Stamboliyskiˮ, “our dear leader, General Hodjeraˮ, etc.[16] Poems and stories were written in his honor and used as party propaganda. Oskar Tartalja wrote that the borbaši had two ideals: their program and Hodjera, who was portrayed as a true leader. Oskar Tartalja extolled him as follows: “and when the whole nation, or at least the majority, learns and realizes this, then our leader will become the leader, ideal and idol of the entire people!”[17] Although, at least according to textual evidence, the personal cult of Svetislav Hodjera was very pronounced, the borbaši were not blindly loyal to him, as evidenced by numerous rifts in the party and allegations leveled against the “The Leaderˮ. In 1936, the party became bitterly divided about joining a coalition with other movements that championed integral Yugoslavism (Yugoslav National Movement – ZBOR, Yugoslav National Party, Yugoslav Caucus led by Janko Barićević). Hodjera believed that such cooperation would be harmful to the interests of JNSb, while Miloš Dragović, one of the party’s founders, argued that it would be beneficial to join forces with them. After several months of secret talks, the borbaši ultimately turned down this cooperation, and Miloš Dragović and his close associates were expelled from the party.[18]

With his ever more frequent confrontations with the United Opposition and JNS, Hodjera grew closer to Prime Minister Milan Stojadinović and his Yugoslav Radical Union (JRZ). The talks between Hodjera and Stojadinović must have begun before September 1938 because, on September 2, Stojadinović informed Prince Paul that cooperation with Hodjera seemed likely. The agreement was reached by the end of the month, and Hodjera entered the government on October 10, 1938, as a minister without portfolio.[19] Hodjera and JNSb ran in the elections of December 11, 1938, on Stojadinović’s electoral list, winning two seats in the parliament. These deputies were Damnjan Trbušić and Živan Lukić, but Hodjera won just 995 votes in the county of Homolje, less than Dušan Pantić, the candidate of JRZ, and Mirko Urošević, the JNS candidate.[20] In line with the previous agreement, Hodjera nonetheless became a member of the newly formed cabinet; ten days later, Stojadinović informed him that he was no longer a cabinet member due to a reshuffling in the government but that he hoped that “their friendship would remainˮ.[21] At the same time, both JNSb deputies left the party and joined JRZ. With this move, Stojadinović essentially destroyed JNSb. Hodjera and his comrades never recovered from that blow. The party no longer had any representatives in either the parliament or the cabinet, and after years of rifts and frictions, its membership had dwindled drastically. The borbaši later reconciled with Stojadinović after his defeat and even discussed a joint action against the new Cvetković–Maček government.

The information about Hodjera’s post-1939 fate is very scarce. He seems to have shared the fate of the party he had founded and led. The Cvetković–Maček Agreement, which established the Banovina of Croatia, marked the end of all concepts advocated by JNSb, and the party began to crumble under regime pressure. With a handful of his most loyal associates, Hodjera continued to hold JNSb meetings in his own home and issue statements reported by a couple of newspapers. The available sources mention Hodjera for the last time on September 15, 1940.[22] His fate during World War II is also fairly obscure. Branko Petranović states that he spent the war in a German camp and came home in 1945.[23] German documents report that he was interned as an officer of the Yugoslav army. The occupiers considered releasing him and allowing him to return to the country to be given a role in the collaborationist administration but ultimately abandoned this plan, judging Hodjera’s reputation among the people as inadequate for such a task.[24] There is more information about his son, Zoran, who joined Dragoljub Mihailović’s troops as a member of the Democratic Youth and fought with them on Kopaonik, where he was wounded. After the end of the war, Svetislav Hodjera disappears from the historical stage. None of the members of the Hodjera family attended the first shareholders’ meeting of the Association for Air Travel on July 2, 1945, although he had been a shareholder.[25] Hodjera is known to have died after the liberation, but there is no information about either the date of his death or the place where he was buried.[26]

[1]С. Микић, Историја југословенског ваздухопловства, (Београд: б.и, 1932), 456.

[2]Naša krila, 1. 10. 1924.

[3]V. Vojinović, Srpsko vazduhoplovstvo 1916-1917 prema knjizi depeša No. 1, (Beograd: S. Mašić, 1996).

[4]Архив Југославије (АЈ), Посланство Краљевине Југославије у Мађарској – Будимпешта, 396-1-1,Молба Светислава Хођере, 9.6.1920.

[5]Г. Маловић, „Светислав Хођера – манифестациони заточеник Југословенства“, Српске органске студије, бр. 1, 2002, 271-277.

[6]Аnonim, Pravila društva za vazdušni saobraćaj. (Beograd: b. i, 1927); Anonim, Izveštaj upravnog i nadzornog odbora o radu, ( Beograd: b. i, 1929).

[7] АЈ, Југословенска народна странка – борбаши, 307, 1, Биографија Светислава Хођере.

[8]АЈ, 307,1, Биографија Светислава Хођере.

[9]Политика, 16. 10. 1931; М. Сокић, Статистика избора народних посланика, (Београд: Југославија, 1935), 181; Ч. Митриновић, Прво Југословенско народно представништво, (Београд: Ч. М, 1931), 109.

[10]АЈ, 307,2, Политичка ситуација;АЈ,307,2, Господо и драги пријатељи.

[11]Споменица борбаша (Београд: ЈНС, 1938).

[12] Cf. Т. Stojkov, Opozicija u vreme šestojanuarske diktature, (Beograd: Prosveta, 1969), 302-305; Д. Јовановић, Политичке успомене, књ. 3, (Београд: Архив Југославије, 2008), 110-117.

[13] АЈ, 307,1, Резолуција Извршног одбора 24. 04. 1935.

[14]Вечерње новости, 26. 7. 2003.

[15]Cf. F. Čulinović, Jugoslavija između dva rata, knj. 2, (Zagreb: JAZU, 1961), 39; Contemporary Yugoslavia, Wayne Vuchinich, ed., (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969), 356; Т. Кулић, "Српски фашизам и социологија", Социологија, 16(1974), 240; Г. Маловић, „Светислав Хођера – манифестациони заточеник Југословенства“, Српске органске студије, бр. 1, 2002, 271-277.

[16]АЈ, 307,2, Борбашима среза параћинског; АЈ,307,2, Борбашка песма Љубе Новаковића из 1936. године; АЈ, 307,2, Јово Т. Смиљанић, Три песме и приповетке о Светиславу Хођери вођи Борбаша.

[17]О. Тартаља, „Хођера! Хођера! Хођера!“, у: Споменица борбаша, (Београд: ЈНС, 1938).

[18]Правда, 17. 7. 1937; Време, 20. 7. 1936.

[19] АЈ, Збирка микрофилмова 797, Микрофилмована збирка кнеза Павла, ролна 04 снимак 505-507, 511- 512.

[20]Политика, 8. 12. 1938.

[21] АЈ, Збирка Милана Стојадиновића, 37-47-304, Писмо Стојадиновића Светиславу Хођери 21. 12. 1938.

[22]АЈ, Централни пресбиро Председништва Министарског савета, 38-352-500, Седница извршног одбора борбаша; АЈ, 307, 1, Седница Изршног одбора Борбаша 15. 09. 1940.

[23] Б. Петрановић, Историја Југославије 1918-1988, I, (Београд: Нолит, 1988), 282-283.

[24]Историјски архив Београда, Заповедник полиције безбедности и службе безбедности, Досије Светислава Хођере (H-37).

[25] АЈ, Министарство трговине и индустрије Краљевине Југославије (65), 1230, Састанак акционара 2. 7. 1945.

[26]Д. Јовановић, Политичке успомене, књ. 12, 368-369.